In the present day, it’s virtually impossible to envision the global wine market without the vibrant presence of South American wines. Walk into any wine store in North America, one not exclusively dedicated to a specific region, and you’ll undoubtedly find Chilean and Argentinean wines gracing its shelves. Yet, a mere two decades ago, the prospect of encountering South American wines outside of South America was an exceedingly rare occurrence.

The roots of viniculture, entwined with European vines, were firmly planted in South America as far back as the 16th century. These vines arrived with immigrants from Spain, Portugal, and Italy, individuals who possessed the knowledge and expertise required to cultivate grapes and craft wine. South America, blessed with a multitude of regions perfectly suited for viticulture, never lacked for those who appreciated the pleasures of the wine.

However, it would be a stretch to suggest that South Americans were particularly concerned with the quality and refinement of their wines. These were straightforward, house wines, with no aspirations of global recognition. A significant portion of the grape harvest was destined for pisco production, as detailed here.

It wasn’t until the tail end of the 20th century that South American winemaking, as we understand it today, truly came into its own, rapidly establishing a firm foothold in the international wine arena.

Of course, every region awakens from its slumber at its own pace. Brazil, Bolivia, Venezuela, and Peru are still in the reverie stage, continuing to produce basic, locally consumed wines, albeit with some early stirrings of change on the horizon.

Uruguay, however, stirred from its slumber a few years ago, took note of how far Chile and Argentina had advanced, and decided to hasten its pace. And quick it was. While Uruguayan wines were considered exotic in the North American market just five years ago, today, the flagship wine of Uruguay, the robust and full-bodied Tannat, can be found without any difficulty. More details about Tannat, the grape of French South-West that has found a new motherland in Uruguay can be found here. For aficionados of powerful red wines, the allure of Tannat is worth exploring further.

At the heart of this burgeoning industry lie two key players: Argentina and Chile. Argentina, the larger contributor to the world wine market, and Chile, a nation that has swiftly ascended to meet the highest global quality standards, share the spotlight.

Argentina

Argentina’s love affair with winemaking spans over five centuries, dating back to the arrival of vines in Mendoza in 1557 from Santiago, Chile, a region nestled just across the Andean mountains. For 300 years, Mendoza quietly produced wines primarily for local consumption, a status quo that shifted in 1857 with the construction of the railroad connecting Mendoza and Buenos Aires. This newfound accessibility ignited an expansion of wine production to quench the capital’s growing thirst for wine. In the 1950s, Moet et Chandon, a renowned Champagne house, noted for its global reach, extended its presence to Argentina, marking the genesis of Argentine sparkling wine production. The 1990s saw a significant transformation, as Argentina transitioned from a military dictatorship to an open market economy, which attracted foreign investors to the wine sector. The devaluation of the peso in 2001 further accelerated this shift. This period marked the advent of modern Argentine winemaking. Today, Argentina stands as the world’s fifth-largest wine producer and the tenth-largest wine exporter.

What makes Argentina particularly conducive to winemaking? Chiefly, its majestic mountains provide the answer. Creating exceptional wine requires a specific set of conditions. Grapes thrive on warm, sun-drenched summers and, crucially, dry and sunny autumns that allow grapes to ripen fully while preventing the growth of mold. Yet, excessively hot weather can result in wines with a cloying, jammy taste, overshadowing their delicate aromas. In such instances, cool nights can come to the rescue. Further, grapevines require the respite of winter. Vines thirst for water, but the soil should possess impeccable drainage – the fussiness of wine grapes is indeed remarkable. Argentina encompasses all the necessary elements; the country’s bountiful offering of hot, sunny days and cool nights, accompanied by the abundance of glacier-fed water and well-drained sand and granite soils, creates the perfect environment for viticulture. These conditions, however, exist mainly in the elevated mountainous regions. The lower regions tend to be excessively hot, thus lending themselves to other agricultural pursuits.

As for grape varieties found on Argentine vineyards, while international grapes like Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, Chardonnay, and Viognier do have their place, Argentine wines truly shine through their featured varietals: Torrontes, Malbec, and Bonarda.

Torrontes is an emblematic Argentine white wine variety, a distinctive hybrid of Muscat of Alexandria and Criolla Chica. In days gone by, Torrontes was cultivated at lower altitudes to boost productivity. Regrettably, the wine from these conditions turned out to be uninspiring. However, a shift to higher altitudes with limited irrigation has transformed Torrontes into a medium-bodied wine brimming with a lively, fruity-floral bouquet and vibrant, refreshing acidity. More details about Torrontes can be found here.

Bonarda, another Argentine specialty, has historically been used primarily in blends and was not associated with high-quality wines. Yet, modern viticultural approaches have unveiled its unexplored potential.

However, the crown jewel of Argentine winemaking is undoubtedly Malbec. The grape’s original home is France, specifically Cahors, a small region in the south of Bordeaux known for its specialization in Malbec. In 1869, France generously gifted Malbec vines to Argentina. Nevertheless, the Argentine Malbec has distinctive qualities due to the use of specific clones more suitable for the local climate. The warmer climate also imparts a unique character to the wine’s flavor.

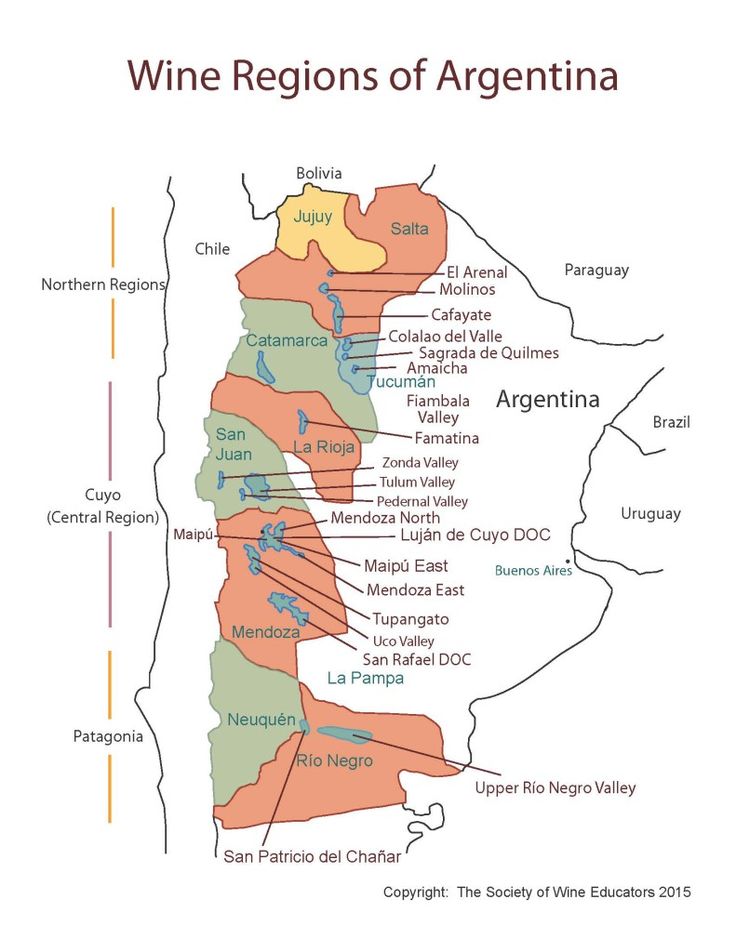

Argentina boasts seven primary wine regions, each with its own unique specialization and standout varietals worth exploring.

Salta – The northernmost and highest wine region. Vineyards here are situated at elevations ranging from 1750 to 3100 meters, once the highest vineyards globally before Chile claimed that title. The extreme climate fosters wines with a distinct, rich, and complex taste. Salta is renowned for producing some of the finest Torrontes, and its cold nights preserve the aroma in its white wines. Its Malbec, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Syrah are highly regarded, especially by those who appreciate an old-world style.

Catamarca and La Rioja – Currently focused more on quantity than quality, these regions produce a surplus of affordable and straightforward wines, with modest attempts at changing this trajectory.

San Juan – A rather hot region, which can make the quest for quality more challenging. Nevertheless, it produces noteworthy Syrah, a grape variety that thrives in warmer climates.

Mendoza – The largest viticultural region, responsible for over 70% of Argentine wine production. Grapes grow in a high-altitude desert environment, yielding impressive results. Mendoza is divided into three distinct sub-regions, though these are not always mentioned on the label.

• Uco Valley – Known for its high vineyards, ranging from 1000 to 1450 meters. This region is now dedicated to enhancing wine quality. When the Uco Valley is noted on the label, it’s a positive indicator. The region is also conducive to white wine production.

• Lujan de Cuyo – A region increasingly known for its Malbec production. Wines here tend to be gentle, balanced, and spicy.

• Maipu – Home to many vineyards with old Syrah, Malbec, and Cabernet Sauvignon vines, resulting in wines of particular interest. However, the region also generates an abundance of simple, inexpensive wines, so discretion is advised.

In the southern part of the country, the coolness of the region is not provided by mountains but by the cold breath of Antarctica. Patagonia has two wine-producing regions – Neuquen and Rio Negro, which provide ideal conditions for grapes requiring a cooler climate, such as Pinot Noir and Sauvignon Blanc.

Chile

Chile’s wine history stretches back to the 16th century, when grapevines first graced its fertile soil. For the most part, Chileans crafted wines for local consumption, paying little heed to quality. Concerns arose in the 1970s as winemakers began to worry that their products couldn’t compete with the world’s finest. However, substantive strides toward improvement didn’t commence until the 1990s, coinciding with Chile’s transition to a more open economic system following the era of Pinochet. Although this shift was belated, it was swift and remarkable.

Chile’s climate is a winemaker’s dream. Its numerous valleys, nestled between mountain ridges cascading from the Andes to the Pacific, enjoy an abundance of sunshine and warmth. The essential touch of coolness is provided by snow-capped mountains on one side and the Pacific Ocean, with its cold Humboldt currents, on the other. The soil is ideal for grape cultivation, and, intriguingly, the phylloxera pest that ravaged European vineyards in the 19th century cannot survive in Chile’s terroir. Chile stands as one of the rare countries where Vitis vinifera can thrive without the need for American rootstock.

Chile’s wine repertoire is extensive and noteworthy. The heavyweight here is Cabernet Sauvignon, which accounts for nearly half of all red grape varieties. It spans the spectrum from simple, fruity renditions to full-bodied, complex wines. Cabernet Sauvignon is not only presented as a varietal wine but is also used in blends with Merlot, Carmenere, and Syrah.

Merlot vines are plentiful, mostly destined for affordable, medium-bodied wines celebrated for their fruity aroma. These wines are popular on the global stage.

Carmenere is the story of Chilean viticulture. Originating from Bordeaux, France, this late-ripening grape variety seldom reached full ripeness in the Bordeaux climate, so it played a minor role in blends primarily for flavor enhancement. During the phylloxera epidemic in the 19th century, Carmenere in Bordeaux nearly vanished. Consequently, French winemakers opted not to replant it. In Chile, Carmenere vines arrived just before the phylloxera epidemic struck, but this was unbeknownst to them. They planted Merlot vines, crafted Merlot wines, and continued to sell them despite the peculiar taste. Eventually, it was discovered that these vines were a mix of Merlot and Carménère. Only in the 1990s, during a new era for Chilean viticulture, was the mysterious taste of their Merlot deciphered, leading to the separation of the vines. Since then, they have grown Merlot as Merlot and Carménère as Carménère. In Chile’s sunny climate, Carménère ripens fully, offering an intense flavor profile of black fruits, complemented by herbal and red pepper aromas. Carménère is now a hallmark of Chilean wines. More details about Carménère can be found here.

The first Syrah vines were planted as recently as 1996, but the favorable climate has enabled Chile to produce excellent Syrah wines, particularly in the northern regions.

Chile’s cooler southern regions have been successful with Pinot Noir.

Traditionally, Muscat of Alexandria dominated the white varieties and was largely used for Pisco production. Nowadays, Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay are the primary white grape varieties.

The Sauvignon Blanc journey in Chile mirrors the Carmenere saga. Chileans, with their flair for surprises, initially grew Sauvignon Blanc, crafting wines with a unique flavor. As it turns out, they had been nurturing a blend of Sauvignon Blanc and Sauvignonasse. After deciphering this mystery, they have successfully produced Sauvignon Blanc in cooler regions.

Chile established its wine laws in 1994. These laws, much like those in other New World countries, define Denominaciones de Origen (DO), only specifying regions. According to Chilean law, a DO can be indicated if 75% of the grapes come from the region, while EU laws demand 85%. To cater to export requirements, most Chilean producers opt to maintain the 85% threshold. Besides the region, these regulations offer little information about the wine’s quality.

Chile has also adopted the traditional Spanish system for wine quality, including categories like Reserva, Reserva Especial, Reserva Privada, and Grand Reserva. Interestingly, these designations borrow the names but not the underlying system. These classifications have no additional requirements beyond six months of aging in oak barrels. Beyond this, the labels provide little information about the wines’ character or quality. Therefore, comparing wines based on this system is most useful when confined to a single winery.

Chile’s wine regions, while not always prominently featured on labels, are significant. Here is a brief tour, starting from north to south:

Coquimbo straddles the boundary of the Atacama Desert, boasting the country’s highest vineyards, perched at elevations up to 3500 meters. This region used to grow grapes mainly for sustenance and pisco production. At the close of the 1990s, it was divided into three elite sub-regions: Elqui, Limari, and Choapa. These areas contribute just 2% of all Chilean wines, yet they produce some of the nation’s finest. Each sub-region consists of a separate valley with its own distinct climate, but they share a common climate feature: intensely sunny days during the summer and cold nights due to glacial mountain air. While limited rainfall necessitates irrigation, the extraordinary results more than justify the effort.

• Elqui Valley yields exceptional Sauvignon Blanc and Syrah, with its granite soils and climate reminiscent of France’s Northern Rhône, the Syrah’s original home.

• Limari, located slightly south and closer to the ocean, enjoys cooling from ocean fogs. It has garnered acclaim for Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, and Sauvignon Blanc.

The Aconcagua Region comprises three sub-regions: Aconcagua, Casablanca, and San Antonio. Among them, Aconcagua is the hottest, in fact, the warmest in the country. One of the oldest wine regions, Aconcagua, is also the first region to cultivate Syrah. The region is renowned for its red wines, predominantly Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah, and Carmenere, especially for those who favor the traditional Chilean style, characterized by fruit-forward, high alcohol, and tannic wines.

• Casablanca and San Antonio are situated nearer to the ocean, benefiting from nightly fogs and daytime breezes. These are the only Chilean regions where white wines surpass reds. These areas excel in producing Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, and Pinot Noir. In San Antonio, special attention should be paid to the Leyda region.

The Central Valley Region is a warm, flat expanse with abundant irrigation near the capital. Consequently, most vineyards are concentrated here, making it the largest volume producer of Chilean wines. The region is divided into four sub-regions: Maipo, Rapel, Curico, and Maule.

• Maipo is the heart of Chilean wine production due to its proximity to Santiago. Its best vineyards are perched on the Andes’ slopes. Maipo is famed for its Cabernet Sauvignon, often distinguished by a subtle minty aroma.

• Rapel, a vast and diverse sub-region, is located to the south of Maipo. It is split into two zones, Cachapoal and Colchagua, with the latter dominating the labels due to its ocean-influenced climate. Colchagua is renowned for its robust, full-bodied red wines, particularly Cabernet Sauvignon, Carmenere, and Syrah.

• Curico and Maule, for now, predominantly produce simple, inexpensive blends.

The southernmost regions, Itata and Bio-Bio, are greeted by the chill from Antarctica. These areas are ideal for cool-climate-loving varieties like Pinot Noir,

Chardonnay, and aromatic whites such as Gewürztraminer and Riesling.