October 1st marks World Sake Day, a celebration of this revered Japanese libation.

This introductory article endeavors to unveil the technological intricacies of sake production and shed light on the valuable information concealed within the sake bottle’s label.

Sake, the iconic Japanese alcoholic beverage, is often simplistically labeled as “rice wine” or “rice vodka.” While there’s no dispute regarding the inclusion of “rice” in these descriptions, it’s crucial to recognize that sake stands apart from both vodka and wine. Unlike vodka, whisky, brandy, or tequila, sake does not undergo distillation in its production. Similarly, it diverges from wine, which is the result of fermenting fruit and berry sugars using yeast.

Sake Production: Where Rice Meets Craftsmanship

Technically speaking, sake bears a closer resemblance to beer in terms of production. It involves a double fermentation process: the first is the conversion of sugar into alcohol by yeast, a fundamental step in alcohol production. The second phase revolves around liberating sugar from the starch present in grain. However, sake’s journey takes a markedly different route. Unlike beer, where barley enzymes break down the starch during the malting process, sake’s starch conversion process is truly unique. Sake stands apart from rice enzyme-driven processes, as it’s made from milled and steamed rice, rendering rice enzymes irrelevant. Instead, sake relies on the enzymatic prowess of a special fungi called koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae), a close relative of the mold famously used in penicillin production.

The sake-making process can be succinctly summarized as follows: rice is cultivated, harvested, polished, and steamed. A quarter of this rice is carefully seeded with koji mold. As the mold starts to flourish, it’s seamlessly combined with the remaining rice, along with water and yeast, marking the initiation of the process.

After a delicate three-day balancing act of components, a 20 to 30-day fermentation period commences. Unlike beer, where fermentation processes are sequential, sake sees these processes running concurrently. Upon the completion of fermentation, the sake is meticulously filtered, then bottled, resting for approximately six months before it reaches its prime for indulgence.

Deciphering Sake Price Diversity: Beyond Rice

The wide-ranging prices of sake can be a labyrinth to navigate, but there’s a simple and significant place to start: rice. However, it’s important to recognize that the rice used in sake production differs significantly from the rice varieties we commonly find on our dining tables, much like the distinction between wine and table grape varieties.

Sake rice boasts a size advantage, typically around 30% larger than table rice. But this isn’t the defining difference. In table rice, starch, fats, and proteins are uniformly distributed throughout the grain. Sake rice, on the other hand, was carefully cultivated to concentrate starch at the grain’s core, with fats and proteins residing on the grain’s periphery. Although this division isn’t absolute, it’s substantial. A glance at a sake rice grain reveals a core rich with starch and an outer layer with a translucent blend of everything else.

Interestingly, sake rice commands a price tag three times higher than its table rice counterparts and, much like wine grapes, it remains untouched for culinary purposes.

Sake rice comes in numerous varieties, each distinguished by unique aromas in the finished product, further contributing to price disparities.

The milling process, which involves removing the outer layers of rice (fats and proteins), is another price determinant. The more removed, the better the taste. Premium grades often entail the removal of up to 65% of the grain. This meticulous milling guarantees the absence of earthy flavors, instead favoring floral and fruity aromas.

The final factor in price variability is the balance between traditional craftsmanship and automated processes, especially in koju seeding and ingredient mixing. Typically, meticulous, hands-on regulation by a master brewer yields a higher-quality product, albeit at a higher cost.

Beyond the Brew: Sake’s Many Facets

But what else contributes to the diverse world of sake?

Alcohol: Post-fermentation, sake naturally reaches an impressive 19-20% alcohol by volume (abv), an exceptionally high figure for yeast. However, this is often diluted to a milder 15-16% abv to enhance its flavor. As for adding distilled alcohol, in futsu-shu, the humble table sake, it’s common for cost-cutting purposes. However, premium sake, regardless of grade, falls into two categories. Junmai, the first category, never sees the addition of distilled alcohol. The second, which allows a small amount of distilled ethanol at the end of fermentation, serves to stabilize the brew and extend its shelf life without significantly altering the flavor.

Sugar: Like wine, sake can vary in sweetness. Its sweetness is measured on a scale called nihonshu-do, ranging from -3 (sweetest) to +12 (driest). While +4, often found in non-Japanese markets, is a popular choice, other variations exist to cater to diverse palates.

Aging: Sake typically hits its peak after six months and maintains its quality for about a year. Although some experiment with aging, the results haven’t been groundbreaking. Thus, sake is best enjoyed while young.

Serving Temperature: Traditionally, futsu-shu (table sake) is gently warmed, while premium sake aligns more with white wine, best served chilled at around 7-8°C. However, there’s a contemporary trend to lightly warm premium sake, so the choice ultimately rests with your palate. In my view, chilled sake emphasizes floral notes, whereas warming brings out alcohol and earthy undertones. I lean toward chilled sake myself.

Storage of Open Bottles: Sake displays a bit more resilience to oxygen than wine and can survive in the refrigerator for up to a week.

Lastly, let’s touch on classification. While it’s a rather loose system with blurred boundaries between grades, it provides a helpful framework for understanding the diverse world of sake.

| With distilled alcohol | No distilled alcohol | Requirement to rice milling | % of the entire market | |

| «Premium sake» Quality, aroma, complexity, and price increase in types from the bottom to the top | Daiginjo-shu | Junmai-Daiginjo-shu | At least 50% milled away, often as much as 65% | 3.9 | 3.3 % |

| Ginjo-shu | Junmai-Ginjo-shu | At least 40% milled away | 3.9 | 3.3 % | |

| Honjozo-shu | Junmai-shu | At least 30% milled away | 12 | 7 % | |

| Normal «table» sake | Futsu-shu | No minimum requirement | 74% | |

The vast majority of sake falls into the Futsu-shu category, which is essentially table sake. While you can certainly stumble upon some excellent examples within this category, choosing randomly can be a bit like a roll of the dice, yielding unpredictable results.

The quality of premium sake, on the other hand, is stringently regulated by laws pertaining to sake type and rice milling levels. Among premium varieties, the four types featuring the word “Ginjo” in their names occupy a somewhat fluid space, with subtle differentiations. These sakes tend to be gentle, boasting distinct floral and fruity aromas, and they’re notably devoid of earthy notes or a pronounced alcohol taste. A good taste experience is practically guaranteed, but be prepared for the premium price tag that accompanies these refined flavors.

There’s also a niche world of specific sake variants produced in small quantities to cater to enthusiasts. For instance:

•Nigori-zake: This is akin to non-filtered, cloudy sake, reminiscent of unfiltered beer. It features a rich, creamy character along with yeast-fungi sediment.

• Nama-zake: Here, we have non-pasteurized sake. Although the taste doesn’t significantly differ from pasteurized versions, it cannot be stored and must be consumed fresh.

• Genshu: Genshu is non-diluted sake boasting an alcohol content of 19-20%, packing quite a punch.

• Koshu and Choki Jukusei-shu: These sakes are aged, showcasing how sake can develop complexity and depth over time.

• Sparkling Sake: While not exceptionally popular and relatively new to the market, sparkling sake is a delightful existence worth exploring.

So, as you journey through the world of sake, remember that quality varies significantly, and understanding the terminology can greatly enhance your appreciation of this diverse and nuanced libation.

Example of higher category’s premium sake:

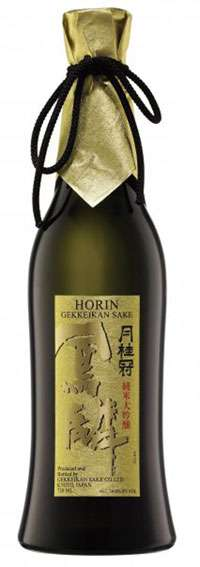

Gekkeikan Horin Sake

Prefecture: Kyoto, Japan

Region: Fushimi

Alc./Volume: 16.6% (720ml) 15.5% (300ml)

Size: Available in 720ml & 300ml

Class: Junmai Daiginjo

Sake Meter Value: +2

(photo from maker’s site)

Visit my online store for a unique poster featuring this cocktail, along with many other beautiful cocktails and other wine-related subjects.

It’s the perfect way to add a touch of sophistication to your kitchen or bar. Click here to shop now!