Unfortunately for wine lovers, USA does not have similar to EU requirements for winemakers. Labels on US wines provide little to nothing information, nonetheless some of it can still be helpful.

Even though European immigrants brought grape vines to American continent long time ago, reasonable winemakery developed in the US only in the mid-twentieth century. Prior to that, usual troubles, such as phylloxera, Prohibition and others occurred on a regular basis. Then it had gradually diminished. At last, currently, the US winemakery is on the ascent (as most of the other wine world). Nowadays, all 50 American states, including Alaska, produce wine. As a matter of fact, some of them use different fruits more often than grape, or they buy grape from other states; it is a fact, that wine produced in any state can now be found on the market. Yet, only four states: California, Washington, Oregon, and New York, represent valid interest to wine lovers.

Wine laws (as any other laws) exist in the USA on two levels: state and federal.

State wine laws don’t bring anything principally new, but only specify numbers, so let’s first look what does federal law say.

If PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) in the EU regulates territory as well as quality of grape growth and wine production, then American law applies only to territory. Nobody cares what winemaker grows and how he makes his wine.

A place can be specified in political boundaries as a state or a county. In this case a state (California, Washington, New York, etc) or a county (Napa, Monterrwy, etc) would be printed on a bottle label. It only means that particular wine was produced in that state or county. None other information is available, even the region of the grape growth.

In 1980, the USA finally introduced the concept of AVA, American Viticultural Area, the light shade of European PDO. An AVA title can be obtained by any winery region that had approved its winemakery peculiarities. AVA can cover territory of any size, from a little one on a single vineyard, to a huge one that covers a quarter of California. AVA doesn’t depend on political boundaries, for example, Walla Walla AVA covers both Washington and Oregon acres. However, physically AVA territory is seamless.

To put AVA name on their labels, winemakers must comply with the following rules:

-if vintage labeled, 95% of the grape should come from the same vintage

-85% of the grape must be grown on AVA territory

-75% of used grape varieties must be mentioned on a label. Say, if a wine is a blend of 75% Cabernet and 25% of Merlot, only li Cabernet must be mentioned on the label (although, in that case, more often, both grapes would be mentioned, but if a blend is 95% and 5%, the 5%, often, is omitted). If a blend consists of 5-6 grapes, enough varieties should be mentioned to cover 75% of the grape.

-wine must be produced on AVA territory. All used grape must be controlled by the winery, in other words, winemaker can take up to 25% of the grape from non-AVA vineyard, but he must work with this grape on his own winery. It is prohibited to bring wine form non-AVA winery and blend it with local wines.

The numbers vary between states. Thus, Oregon requires the mentioning of 90% of used varieties (against federal 75%), Washington – 85%. New York allows to add up to 25% of non-AVA wine (not only grape) to AVA wine, and so on.

Because AVA doesn’t regulate any other things except once mentioned above, theoretically, AVA title doesn’t guarantee higher and more stable quality of wine. However, in practice, especially in rising wine regions such as Washington, Oregon and New York, winemakers try to appear in their best light, and AVA wines often have good quality and stability.

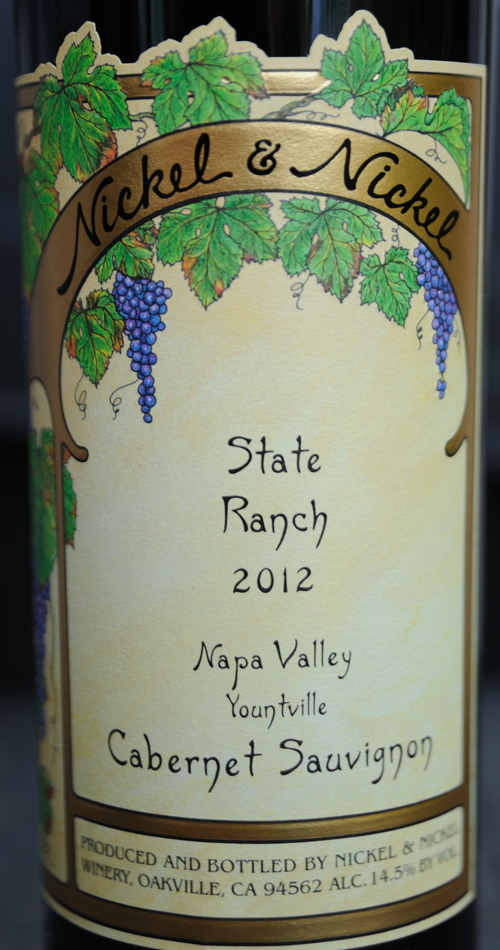

What is inconvenient though, is the fact that the word AVA usually not present on a label. However, if geographical region is mentioned (not in the address of production, but independently in the center of a label, like Walla Walla Valley on a wine from Watermill winery (Washington) or Youngtvill from Nickle & Nickle winery (California) – this is AVA.

Also, keep in mind that Americans traditionally have a habit to name their wines with such famous titles as Chablis or Burgundy. Certainly, these wines have nothing in common with real Chablis or Burgundy, and usually such names are given to cheaper blends. Now, after the adoption of trading agreement with the EU, such names became prohibited to use, but on local market they can still be found. Those wines are usually sold in boxes or big bottles.