The best accompaniment for this article is a glass of good sherry. So, pour yourself some Amontillado or well-aged Oloroso before reading on.

Jerez, also known as Sherry, a name that is more popular in the English-speaking world, is a wine that’s remarkable in many ways. Particularly, Jerez is a wine that connects you to history—you could share your glass of Jerez with an Englishman who lived a hundred years ago, quite literally, without it costing you all the world money. Of course, not every drop in your glass would have mingled with drops from that gentleman’s glass, but some of them truly have. Part of the special charm of Jerez lies in this living connection to the past, beyond its inherent taste qualities.

Fortified wines

Technically speaking, Jerez is a fortified wine, so, let’s make a brief overview of fortified wine in general.

They are traditionally fermented still grape wines to which ethanol is added, either after or during fermentation. The added alcohol halts the fermentation by killing the yeast. If ethanol is added during fermentation, the wine will be sweet, as is the case with Port, Madeira, and Vin Doux Naturel. If ethanol is added after complete fermentation, the wine can be either dry or sweet, depending on the natural sweetness of the base wine. Jerez is produced this way. Pure grape spirit is typically used for fortification, and the final alcohol content usually ranges from 15% to 22% ABV. After fortification, wines are aged to mature and develop their flavors. This is the basic process, and variations of it give us a wide spectrum of flavors, from Port to dry Jerez.

The practice of fortifying wine began as a means to preserve the wine during shipment from Spain and Portugal to England. In those days, wine was transported in barrels by sea, and the journey took many days. The conditions during these voyages were not favorable for wine, which is a delicate substance—long periods of jostling and temperature fluctuations do not improve its taste. High levels of alcohol and sugar helped stabilize the wine, so winemakers began fortifying it. Over time, this preservation method evolved into the creation of new products with unusual and intriguing flavors. Incidentally, the constant tension between England and France greatly contributed to the overall development of winemaking, particularly in Spain and Portugal.

Jerez stands out as one of the few wines that are fortified only after the base fermentation is fully completed.

Jerez, also known as Sherry, is produced in Andalusia, in the southern part of Spain.

Jerez is classified as a PDO wine (read about European Geographical identification system here), meaning it can only be produced within a specific triangular area between the towns of Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, and El Puerto de Santa María. The wine takes its name from Jerez de la Frontera, and its various names—Jerez, Xerez, or Sherry—are legally protected. This means that only wines produced in this designated region, using specific traditional methods, can be called Jerez.

You might come across American fortified wines labeled as “American Sherry” or “Californian Sherry.” However, these are not true Sherry wines—not just because they are made outside the designated region, but also because they do not follow the authentic production methods of Jerez. Therefore, don’t expect to experience the true taste of Jerez when drinking these alternatives.

Now, let’s delve into the unique and complex technology behind Jerez production, which results in a diverse collection of wines with distinct flavors.

Everything begins with the production of the base wine. The Andalusian south is known for its hot and dry climate, coupled with chalky soils that offer excellent drainage. This terroir imparts high sugar content and a specific character to the grapes grown here.

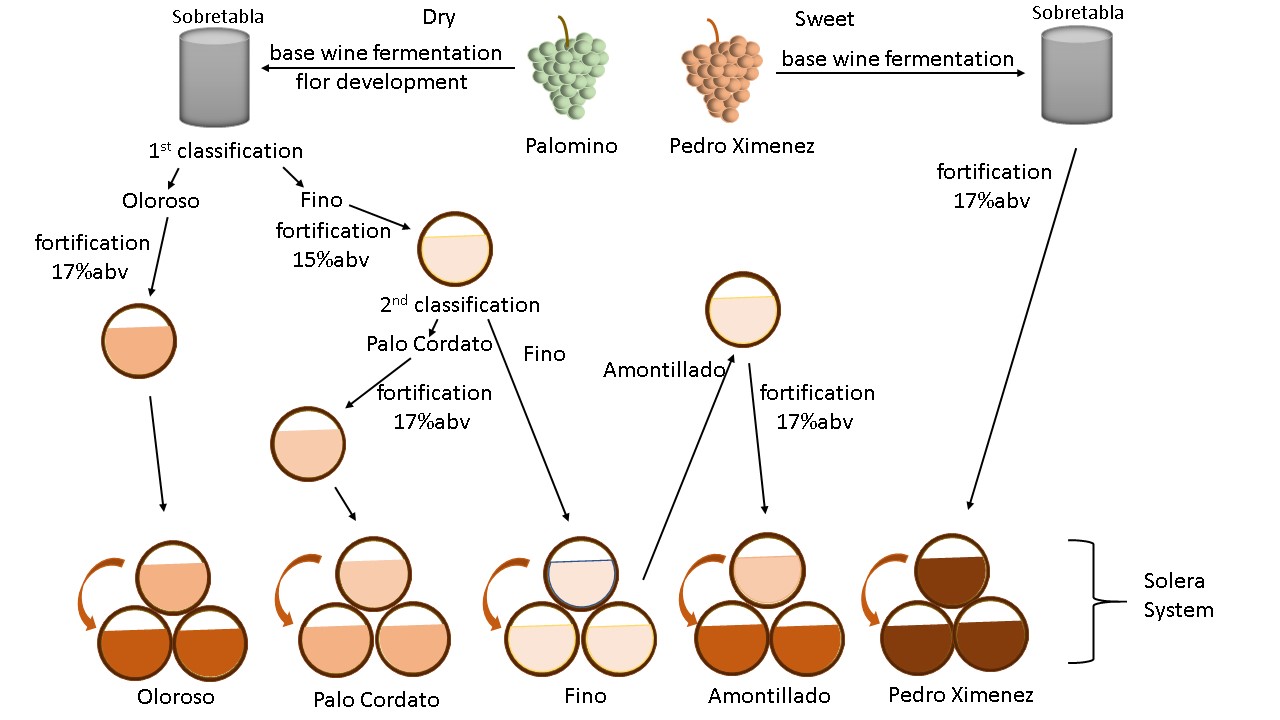

Only three grape varieties are permitted for Jerez production: Palomino, Pedro Ximénez (PX), and Moscatel. Palomino is predominantly used for producing dry Jerez, while PX and Moscatel are reserved for sweet versions. Both Palomino and PX grapes have very subtle flavors on their own, which allows the unique characteristics of Jerez to shine through, particularly those flavors that emerge from the specific maturation process distinctive to this wine.

Vinification

Dry Jerez

After the harvest, Palomino grapes are fermented using a standard process for white wine, with one key difference: the fermentation temperature is higher, typically between 20-25°C. This process produces a completely dry base wine with an alcohol content of 11-12% ABV. Once the sediment is removed, the base wine is transferred to large stainless steel tanks. These tanks are intentionally not filled to the brim, allowing the wine to have good contact with air. At this stage, the wines are tested, and a decision is made regarding which wines are suitable for flor development.

Flor is a distinctive and crucial feature of Jerez. It is a layer of yeast that grows on the wine’s surface in the presence of oxygen. Several different strains of yeast contribute to the formation of flor, distinct from the yeasts used in initial wine fermentation. Typically, wine yeasts live within the wine, consuming sugar, producing ethanol. However, through evolution, Jerez has developed unique yeast strains that have adapted to feed on ethanol instead. These yeasts consume ethanol and glycerol, producing acetaldehydes, which impart the characteristic flavor found in Fino-style Jerez. Additionally, the flor forms a protective layer that shields the wine from oxidation. However, flor is highly delicate and sensitive to temperature and humidity, and it doesn’t always develop successfully. The presence or absence of flor plays the key role in determining the style of Jerez.

Sweet Jerez

For sweet Jerez, only fully ripe bunches of Pedro Ximénez (PX) and Moscatel grapes are harvested, typically through selective hand-picking. After harvesting, the grape bunches are hung on walls in special barns to dry, concentrating the sugars within the grapes and giving the wine a characteristic raisin-like flavor. The sugar concentration in the grape juice becomes so high that yeast cannot ferment it efficiently and quickly becomes inhibited. Although yeast naturally prefers sugar as its primary food source, an excessive concentration of sugar can actually inhibit its activity. As a result, the base sweet wine often has a relatively low alcohol content, around 5-6% ABV. Flor does not grow on sweet wines, so they do not undergo flor formation.

Classification and fortification

Let’s return to the discussion of dry wine. After the base wine is transferred into large tanks, it is classified according to its future maturation path.

There are two fundamental types of Jerez maturation: biological (under flor) and oxidative.

Light-bodied, light-colored, and delicate wines are designated as future Finos. These wines will mature under a layer of flor. Tanks and barrels containing these wines are traditionally marked with a vertical line. On the other hand, full-bodied, dark-colored, and richer wines are classified as future Olorosos, which will mature without flor under oxidative conditions. Tanks and barrels containing these wines are typically marked with a circle. Only the highest-quality base wines are selected for these processes. Wines that do not meet these stringent quality standards are often used for vinegar production or distillation.

At this point, the wine is fortified. Future Finos are fortified to 15% ABV because a higher alcohol content would kill the flor. Future Olorosos and sweet wines, however, are fortified to 17% ABV, which allows them to mature in the presence of oxygen.

After six months to a year, the wine undergoes another evaluation, particularly for those wines maturing under flor. Flor is a delicate and unpredictable phenomenon, and for reasons that are not fully understood, it may fail to develop or may develop poorly. If this occurs, the affected wine is further fortified to 17% ABV and shifted to oxidative maturation. The line marking the barrel for flor maturation is crossed, and the wine is then designated as future Palo Cortado (crossed line).

At this stage, the wine is now known as Sobretabla, and it is ready for the next step in its maturation process. The wine is transferred into 600-liter wooden barrels known as butts. The usage of wood is significant because of its porous nature, which facilitates aeration. However, the extraction of flavors from the wood plays no role in the maturation of Jerez; in fact, it is minimal, especially since these butts have been in use for decades. The barrels are positioned horizontally and filled to about five-sixths of their capacity.

Solera system

The process already seems quite intricate, but the most complex aspect of Jerez production is its unique maturation system. This system is what allows us to share our wine with a Jerez drinker from the 19th century.

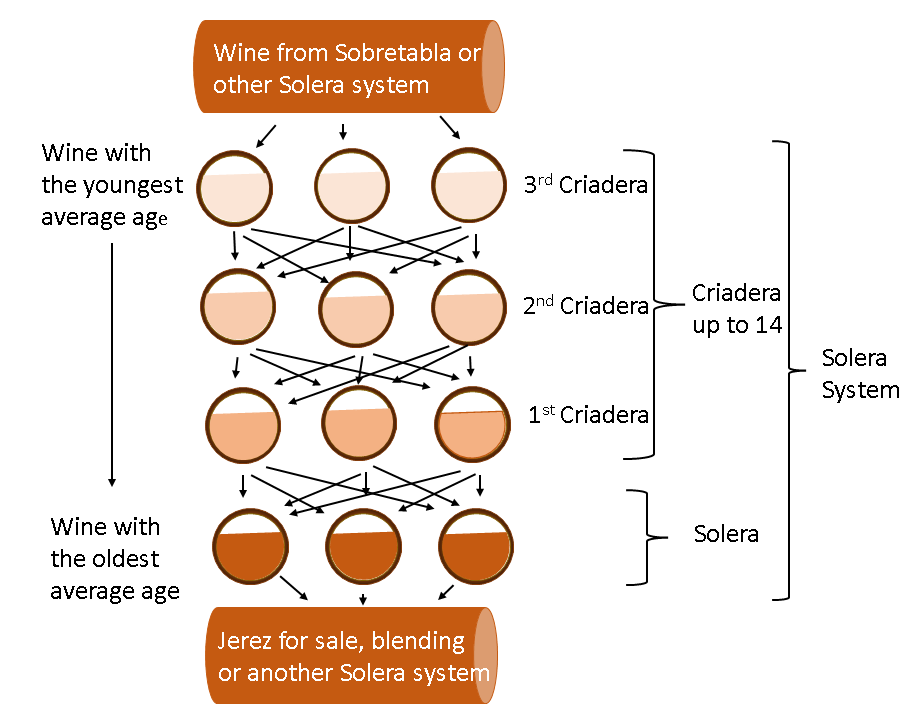

The maturation system is known as the solera. To start, take the fortified base wine, fill a butt (a large wooden barrel), and place it on the floor of the warehouse, known as a bodega. This marks the creation of a new solera. The following year, fill another butt with new base wine and place it above the original one. This process is repeated anywhere from 3 to 14 times, forming the solera system. The lowest butt is referred to as the solera, while the others are called criaderas. There can be anywhere from 3 to 14 criaderas. It’s important to note that the butts from a single solera don’t need to be physically stacked on top of each other—the order in which each criadera is filled is what matters. In fact, it’s common for the criaderas of a single solera to be stored in different buildings to prevent the complete destruction of the solera in case of a disaster.

One solera – one Jerez. When the wine in the first butt (the solera) is ready, the winemaker draws a portion of it—only from the first, oldest butt—for bottling and sale. This portion can range from 5% to 30% of the total volume, with a lower percentage indicating higher wine quality. Taking more than 40% is prohibited by law, but winemakers generally agree to keep 30% as the upper limit. The wine taken from the solera is replaced with the same amount from the second butt (the first criadera). In turn, the wine in the second butt is replaced by wine from the third butt (the second criadera), and so on. In the youngest criadera, the taken wine is replaced with fresh base wine (Sobretabla). This process is repeated each year, and because only a small portion is taken at a time, there’s a high chance that some drops from the solera’s original foundation still remain. This process is continuous, and many existing soleras are well over a hundred years old.

Typically, each criadera or solera in one system consists of several butts, not just one. During the transfer process, wine from the same-age criaderas is blended to ensure uniformity in the taste of the wine from each solera.

The flor, the delicate yeast layer essential for Fino, requires a constant supply of fresh nutrients. These nutrients are replenished as wine from younger criaderas is introduced into the older butts. Without this continuous addition of new base wine, the flor would die. This is why Fino typically doesn’t age beyond seven years. The age of Jerez is a conditional measure, representing the time it takes for the wine to pass through the entire solera system. For instance, if wine is drawn annually from a 3-butt solera, its age will be three years (which is the legal minimum).

Oloroso, in contrast, can be aged for up to 30 years. As it ages, it becomes more concentrated, with its alcohol content rising to as much as 22% abv.

Amontillado deserves special attention. While most Jerez wines, such as Fino and Oloroso, progress through the solera from Sobretabla (the base dry wine) to the final product, Amontillado follows a unique path. It begins as a matured Fino, which is then fortified to 17% abv and undergoes further maturation in an oxidative environment, similar to Oloroso. Amontillado typically spends no less than 12 years in the solera. This dual maturation process gives Amontillado a complex flavor profile that combines the characteristics of both Fino and Oloroso. The longer it ages, the more its taste shifts towards the robust flavors of Oloroso.

Palo Cortado, another noteworthy type of Jerez, is quite rare and can be seen as an intermediate style between Amontillado and Oloroso. It is ideologically similar to Amontillado in that it starts as a Fino before transitioning to oxidative maturation like Oloroso. However, the key difference is that for Palo Cortado, an undeveloped Fino (aged just 1-2 years) is used for this second maturation phase. Sometimes, during Fino’s maturation, the flor unexpectedly dies, leaving the wine unfinished. In such cases, the wine is fortified to 17% abv and switched to oxidative maturation, resulting in Palo Cortado. As producers often say, Palo Cortado isn’t made—it happens. However, these days, some producers may occasionally lend a hand in helping Palo Cortado to “happen.”

Due to the unique maturation system, vintage is irrelevant for Jerez. Instead of displaying a vintage year on the label, you’ll find the year when the solera was founded. The oldest soleras date back over 200 years. For instance, Osborne’s Capuchino solera was established in 1790, and the Amontillado solera de la Riva in 1770.

There is no point in aging Jerez from solera in the bottle, as its taste will not improve with age after bottling. Therefore, once the wine is ready, it is sold immediately or used in blending preparations and sold afterward.

Styles of Jerez:

Jerez can either be the product of a single solera or a blend of wines from different soleras. Wines that are bottled directly from the solera are known as Vinos Generosos.

Jerez wines aged 20 years or more are highly valued and expensive. These include Amontillado, Oloroso, Palo Cortado, and Pedro Ximénez, which can be aged for such long periods. Jerez wines that are 20 years old are labeled V.O.S., which stands for the Latin “Vinum Optimum Signatum” (Wine Selected as Optimal), and which may be conveniently expressed as English “Very Old Sherry.” Jerez wines aged 30 years are labeled V.O.R.S., standing for “Vinum Optimum Rare Signatum” (Wine Selected as Optimal and Exceptional), or in English, “Very Old Rare Sherry.”

Dry Styles of Jerez

Fino – A dry, light-bodied wine with a complex yet delicate flavor. It has a light-lemon color and 15% alcohol content. Fino is matured under flor and has the shortest maturation period among Jerez wines, ranging from 3 to 7 years. Its flavor profile includes almond, bread, and herbs, with a salty note, which is the distinctive taste of flor.

Manzanilla – A subtype of Fino, this wine is the driest and most delicate among Finos. It has a salty flavor and is produced exclusively in Sanlúcar de Barrameda, a seaside town with high humidity and cooler temperatures, ideal conditions for a thick and healthy flor.

Oloroso – This wine is matured without flor, making it full-bodied, heavier, and more intense than Fino, with a dark-brown color. Alcohol content ranges from 17% to 22%. Oloroso has a rich taste of toffee, leather, walnuts, and spices, characteristic of oxidative maturation.

Amontillado – A hybrid between Fino and Oloroso, Amontillado starts as a Fino and is later fortified to 17% alcohol content, transitioning to oxidative maturation. The color ranges from amber to dark brown, and the flavor combines elements of both Fino and Oloroso. Younger Amontillado leans more towards Fino, while older ones are closer to Oloroso. Alcohol content ranges from 17% to 22%.

Palo Cortado – A rare wine similar to Amontillado, but made from a Fino that lost its flor unexpectedly before full maturation. It can be described as an intermediate style between Amontillado and Oloroso.

Naturally Sweet Jerez

Pedro Ximenez (PX) and Moscatel are naturally very sweet wines made from their respective grape varieties, matured only through oxidative aging. These wines can be enjoyed on their own or used in blends. Muscatel has a sugar concentration of 160 g/l, while Pedro Ximenez has 212 g/l.

Moscatel offers dominant floral aromas of jasmine, honeysuckle, and orange blossom, with notes of lime and grapefruit.

Pedro Ximenez has rich flavors of raisins, dates, and figs, complemented by notes of honey, coffee, dark chocolate, cacao, and licorice. Pedro Ximenez is one of the sweetest wines in the world. Despite its extreme sweetness, Pedro Ximenez maintains a fresh taste due to its complex flavor profile,

Typical blends:

For those who appreciate the flavor of dry Jerez but have a sweet tooth:

Pale Cream – A Fino sweetened with concentrated grape must.

Medium Sherry – A blend of naturally sweet Jerez (usually PX) with Fino or Amontillado. These blends are labeled accordingly as Medium Fino or Medium Amontillado.

– The sugar concentration in Medium Sherry can range from 5 to 115 g/l, offering quite a wide spectrum. Wines with sugar levels from 5 to 45 g/l are typically called Medium Dry, while those from 45 to 115 g/l are referred to as Medium Sweet.

Cream Sherry – A blend of naturally sweet Jerez with Oloroso.

Vintage Jerez, known as añada, is very rare. Unlike solera-aged wines, añada matures in a single barrel. Only Oloroso can be made as a vintage wine because flor requires fresh wine to survive, which isn’t possible in a single barrel system.

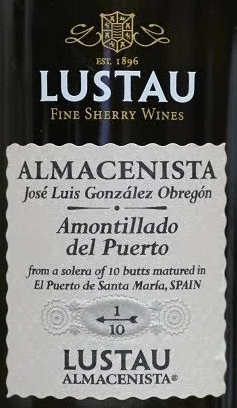

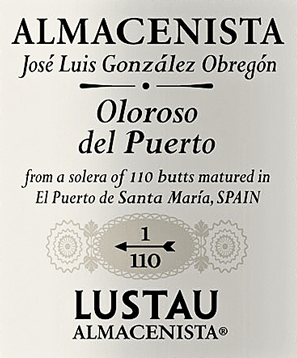

Let’s examine the labels of Amontillado del Puerte from Lustau and Fino from Osborne to understand the key information they provide:

– Year of Solera Foundation:

– The soleras were established in 1896 (Lustau) and 1772 (Osborne), respectively.

– Type of Jerez: Amontillado and Fino

– Place of Solera: El Puerto de Santa María for both labels

– House: Lustau and Osborne**

– Almacenista:

– For Lustau, the almacenista is Jose Luis Gonzalez Obregón

It’s helpful to explain how the Jerez industry is structured:

Historically, Jerez production has been a somewhat fragmented process. Winemakers cultivate grapes and produce Sobretabla (base wine), which they sell to almacenistas. An almacenista owns a solera and produces Jerez. However, almacenistas typically do not bottle and sell Jerez directly to consumers; this is handled by large Jerez Houses.

On the label, you usually see the name of the House. Houses often have their own soleras and can produce Jerez from base wine or purchase partially matured Jerez from small almacenistas to complete the process. They may also buy ready-made Jerez from individual almacenistas to create blends or sell Vinos Generosos. Typically, the almacenista’s name does not appear on the label—only the House name is present. However, sometimes the name of a famous almacenista may be included alongside the House name, as seen in the Lustau label.

Until 1997, individual almacenistas were not legally permitted to sell their own Jerez, at least not in bottled form. Some renowned almacenistas with old soleras operated Tabancos — a hybrid of a tavern and wine shop. These establishments sold Jerez not only by the glass but also by the tap (filling customers’ bottles). Tabanco Obregón in El Puerto de Santa María is an example of such a famous almacenista. Nowadays, individual almacenistas are legally permitted to sell their own Jerez in any manner.

Additionally, the label indicates that the solera Amontillado del Puerte is based on 10 butts, making it a very small and unique solera. In contrast, the solera used to produce the Oloroso on the label is based on 110 butts, which is much larger.

Not all Jerez labels include information about the almacenista or the size of the solera. This is because it is neither required nor applicable to blends.

Serving and food pairing

Fino and Manzanilla best served well-chilled, between 6-8°C.

They are perfectly paired with fish, seafood, cold soups, and salads. Fino also pairs well with olives, nuts, and jamón (Spanish ham).

Oloroso, Amontillado, and Palo Cortado are best served slightly warmer, around 12-14°C.

Amontillado pairs beautifully with soups, white meats, duck, tuna, mushrooms, and cheeses.

Oloroso and Palo Cortado are excellent with red meats and aged cheeses.

These wines are ideal as an aperitif or digestif.

Medium Sweet Blends serve as an aperitif or with Indian or Thai cuisine.

Sweet Jerezes are best served at 12-14°C.

They are ideal as a dessert wine, either on their own or with less sweet desserts like ice cream or dark chocolate. They also pair well with cheeses like Roquefort.

Storage Tips

What if you open a bottle of Jerez and don’t finish it? How should you store it, and for how long?

Keep the bottle in the refrigerator.

Fino and Manzanilla are similar to non-fortified white wines and are best consumed within a day. In Spain, it’s common not to keep them even for a day.

Amontillado, Palo Cortado, Oloroso, and Sweet Wines can be stored in the fridge for several months without notable loss of their quality.

It was an introduction into the wide world of Jerez, which can help you to orient in this world and enjoy it.